National Farmers’ Day and the Unfinished Agenda of Farm Incomes

Krishik Samaj urges Karnataka govt to upgrade Bidar diploma agriculture college into degree college

December 15, 2025

Amit Shah Stresses Cooperative Movement to Boost Sustainable Agriculture and Farmer Prosperity

December 25, 202523 Dec 2025 | Nirmesh Singh

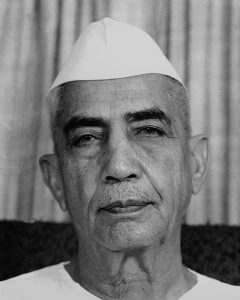

India observes National Farmers’ Day today on 23 December to recognize the contribution of farmers to the country’s food security and  economic stability. The day also marks the birth anniversary of Chaudhary Charan Singh, India’s fifth Prime Minister, remembered for his deep engagement with rural issues and consistent advocacy for farmers’ welfare. Yet, the occasion increasingly serves as a moment of reflection on the distance between policy intent and outcomes in Indian agriculture.

economic stability. The day also marks the birth anniversary of Chaudhary Charan Singh, India’s fifth Prime Minister, remembered for his deep engagement with rural issues and consistent advocacy for farmers’ welfare. Yet, the occasion increasingly serves as a moment of reflection on the distance between policy intent and outcomes in Indian agriculture.

Over the years, government has announced multiple schemes aimed at supporting farmers—ranging from income transfers and crop insurance to infrastructure development and market reforms. Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) are revised annually, and new initiatives are routinely added to the policy framework. However, the core demand raised repeatedly by farmers’ organisations—a legal guarantee of MSP for all major crops—remains unresolved. The absence of such assurance continues to expose farmers to price volatility and market risks beyond their control.

This policy gap becomes more stark when viewed alongside broader fiscal choices. Large-scale write-offs of corporate loans have been justified as necessary for economic stability, while farmer indebtedness persists as a chronic issue. Limited loan waivers, delayed institutional support, and instances of land being auctioned to recover agricultural debt point to a system that has struggled to protect small and marginal farmers. The persistence of farmer suicides underscores the human cost of these structural shortcomings.

A central promise of the current policy discourse was the government’s 2016–17 announcement to double farmers’ incomes by 2022. At the time, NABARD estimated the average monthly income of farmers at ₹8,931, implying a target of approximately ₹18,000 within five years. As the country approaches 2025, there is little publicly available, up-to-date data to assess whether this goal has been met.

In Parliament in the winter session recently, the government continues to rely on the Situation Assessment Survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office during 2018–19. According to this data, average monthly income of agricultural households increased from ₹6,426 in 2012–13 to ₹10,218 in 2018–19. The meagre increase falls short of the stated ambition to double incomes and highlights the absence of recent, transparent assessments of farm livelihoods.

The government maintains that its policy response is comprehensive, citing 28 schemes designed to address challenges such as rising input costs, climate risks, market access, and credit availability. These programmes—ranging from PM-KISAN and crop insurance to infrastructure funds, farmer producer organisations, and digital agriculture initiatives—have expanded the scope of state intervention. However, the effectiveness of this approach is constrained by its fragmentation. Without assured prices, many schemes function as compensatory measures rather than structural solutions to income insecurity.

Policy experts have long argued that the agrarian crisis is rooted in the systematic undervaluation of farm produce. Food and agriculture analyst Devinder Sharma has pointed out that farmers have effectively subsidised the nation by absorbing the costs of keeping food inflation low. In this framework, cultivation often generates losses rather than sustainable incomes, pushing farmers deeper into indebtedness year after year.

The political debate around MSP reflects this contradiction. While few Members of Parliament from different parties including Bhartiya Janta Party and Aam Admi Party have introduced private bills in past seeking an MSP guarantee, there is no broad political consensus. Parties, particularly, Congress that support the idea in principle have hesitated to translate it into legislation, even in states where it holds power. This reluctance has weakened their claims of commitment to income assurance and reinforced farmers’ scepticism.

The movement for an MSP guarantee should not be allowed to dissipate, as assured income remains a critical condition for the long-term economic emancipation of India’s farmers.

_________________________________________________________