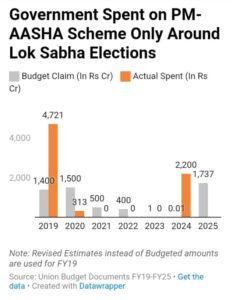

PM AASHA, a crop price support scheme, saw real spending only in the months around 2019 and 2024 Lok Sabha elections. Three years in between the two general elections, the government did not spend a single rupee on the scheme.

Shreegireesh Jalihal & Navya Asopa

New Delhi, 7th May 2024: Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014 after making a series of promises to people. One among them was farmers would get more than half the cost of production as profit. It sounded good.

Then came something better: In 2016, he promised to double farmers’ income in six years. Soon, “doubling farmers income” became the government’s common refrain.

To do that, his government launched a slew of schemes, and repackaged some existing ones.

One of these was PM AASHA or Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyaan, a scheme meant to protect the income of millions of farmers who grow pulses and oilseeds across the country.

Government announced the scheme in September 2018, seven months before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, and claimed to have allocated Rs 15,053 crore. In its press release, the government claimed that this scheme was “henceforth a reflection of Government’s commitment and dedication to our ‘Annadata’”.

Prime Minister Modi, speaking about the scheme in Haryana, touted that “Farmers have been repeatedly asking for this (procurement at MSP) for decades. We have fulfilled their desire now.”

What the Prime Minister didn’t say was that the scheme is the political equivalent of a mash-up of an old but still popular song in a clever new form.

Modi government picked a decades-old UPA-era scheme under which central agencies had been buying oilseeds and pulses worth thousands of crores directly from farmers and added two new components: one, compensate oilseed farmers with cash if they end up selling their produce in the market for less than the minimum support price; two, run pilots to get private players to buy from farmers at MSP.

The new upcycled scheme was sold as a new strategy for doubling farmers’ income under brand PM AASHA.

But data reviewed by The Reporters’ Collective shows the new components of the scheme saw real spending only in the months close to 2019 and the ongoing 2024 Lok Sabha elections in the country, in which close to 55% of the population are engaged in agriculture. In the three years between the two general elections, the government did not spend a single rupee on the scheme.

So, the sporadically funded new components leeched on to the legacy direct procurement scheme that did the heavy-lifting. The pale allocation for the two new features was covered up in Parliament by hiding them behind the broader budget spending of PM AASHA.

In other words, the PM AASHA scheme served solely as an electoral tool to patronise farmers rather than to provide consistent, viable and stable support to them while market prices of crops covered by it crashed.

Ten years later, as Modi faces another election, he and his party aren’t touting the promise of doubling farmers’ income anymore and dropped it from the 2024 campaign spiel.

PM AASHA gives no hope

The compensation & private buyer components of PM AASHA scheme could have supported millions of oilseed farmers who sell most of their produce in the open market where prices have been low for years.

The compensation & private buyer components of PM AASHA scheme could have supported millions of oilseed farmers who sell most of their produce in the open market where prices have been low for years.

In the first six months of the scheme, which had a total outlay of Rs 15,000 crore, the government spent Rs 4,721 crore in compensating oilseed farmers. Of that, the government spent 70% in the two months preceding the Lok Sabha election, which began in April 2019.

All these farmers stood to gain if the component was well-funded each year consistently. But that didn’t happen.

For the next financial year (April 2019-March 2020) the Modi government promised to spend Rs 1,500 crore on the scheme after the elections were over. By May 2019 Modi took oath for the second time as Prime Minister.

But the scheme and its beneficiaries were now neglected. Of the promised Rs 1,500 crore the government spent only 20.8% (Rs 313 crore) on the scheme to support the oilseed farmers.

This was dramatic. The cut from previous year’s expenditure on the scheme was a massive 93%.

It got worse. The Union government did not spend a single rupee to help the farmers under the scheme between 2020-21 and 2022-23.

For the financial year April 2023 to March 2024 the government initially budgeted only Rs 1 lakh for the new components of PM AASHA. But it dawned on the government that elections were again around the corner.

Government data shows the government’s unplanned expenditure on the scheme zoomed up yet again. Against Rs 1 lakh it had initially budgeted, the government estimated it had spent Rs 2,200 crore in the run up to the elections.

Creative Writing

The government’s justification for such swings in its budgetary support to the scheme was it is ‘demand-driven’. When the oilseed farmers face a crisis and sell their produce at lower than minimum prices, they approach the state governments, who then ask the Union government to come to their aid under the scheme.

But, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Agriculture, headed by BJP Parliamentarian PC Gaddigoudar, nailed the government’s lie.

When the Committee asked the Agriculture Ministry about the poor utilisation of funds despite large projected spendings, the Ministry official blamed states for lack of demand in the scheme. The Committee shot back saying the fact that there were no takers for the scheme showed “poor planning” by the government, adding that the scheme had seen “complete non-satisfactory implementation” by the Union government.

Data too, points to the fact that the Union government’s response to assist the farmers was not in proportion to their needs. Between October 2018 and January 2023, the domestic market prices for oilseeds and pulses consistently hovered below the MSP, except for a few months, shows the 2023-24 price policy report for Kharif crops published by the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices. The commission functions under the Union government’s Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare.

Details of such Parliamentary Standing Committee reports and deliberations often do not draw much public attention. Parliamentary debates and questions do.

So, while in closed-door Standing Committee discussions, the government acknowledged the failure of the PM AASHA scheme, in the open house it made up numbers to claim it was a success.

Eleven months after the standing committee report was tabled, two Members of Parliament, Goddeti Madhavi and Dushyant Singh, asked questions about the performance of PM AASHA and spending on the scheme.

They asked, “Why is the Price Deficiency Payment (compensation) component only operational in one state and if the Government has any plans to restructure this scheme?”

The government sidestepped the Parliamentarians’ query by creative presentation of numbers. It clubbed the expenditure of the old direct procurement scheme with those of the new components to show that thousands of crores had been spent at a time when the government had spent nothing on the new components that the Parliamentarians had asked the government about. This was done despite the fact that the budget documents clearly state the expenditure on the PM AASHA’s components separately from the old direct procurement scheme. It’s hard to mix them up.

The compensation component of the PM AASHA is back to perform its pork-barrel role for the 2024 elections. Budget data shows that the government initially did not plan to provide any support to farmers through PM AASHA in 2024. The plans changed after presenting the budget in February 2023, and the scheme has again been ramped up as the country is facing an election.

However, at the same time, the spending on the old direct procurement component plummeted 97.3% compared to the previous financial year, indicating that in the run-up to the 2024 general elections, the Union government has been transferring money to state governments for losses claimed by farmers as opposed to procuring directly from farmers.

____________________________________________________________